Written and medically reviewed by Rich LaFountain, PhD

The history of fasting spans hundreds of thousands of years, and it is deeply intertwined with the story of life on Earth. A closer look into fasting’s expansive timeline clearly shows that it was, and remains, a powerful tool for the survival, health, and wellness of our species.

Read on for a deeper dive into the origins and evolution of fasting, from its start as a necessary part of day-to-day life to its use as a religious and spiritual practice to, finally, its resurgence in modern times as a protocol for longevity and metabolic health.

The Origins of Fasting

Fasting is an ability shared by virtually all animals; the animal kingdom is full of prolific fasters, including reptiles, penguins, bears, and seals, who can abstain from food for months at a time. Bears, for example, perform remarkable feats during hibernation, like achieving a heart-rate reduction of around 80% and a metabolic-rate reduction of 67% from the fed state. Additionally, alternate-day fasting and time-restricted feeding protocols have been shown to improve lifespan and metabolic-health markers in a variety of organisms, including yeast, worms, mice, rats, and, of course, humans.

Fasting physiology is built into the survival of our species. Prior to the agricultural revolution around 10,000 BC, food was not readily available, and even dangerous to procure. As such, early humans had to adapt to long stretches of time without eating — a sort of involuntary, but essential, form of fasting. Each individual hominid that made it to adulthood probably experienced involuntary fasts for days or weeks with some regularity.

Evidence suggests that, when there were much more distinct feeding-fasting cycles and greater physical activity levels, that people survived, and perhaps even thrived. Reliable, constant access to food is an incredibly new development if you consider the scope and timeline throughout all of human history. According to the thrifty-gene hypothesis, round-the-clock access to food may be contributing to contemporary obesity and metabolic-health challenges.

Ancient and Religious Fasting

People of nearly every culture have participated in purposeful fasting for spiritual or health reasons. Nearly every major religion developed their own fasting rituals to support the spiritual development of their members. Ancient fasting practices first emerged around 1,500 BC with the Vedic, Hindu, and Jainism religions. Fasting on designated holy days was a common practice to reduce the burden and harm that harvesting and eating caused for both animals and plants.

The founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama, also fasted in an effort to achieve enlightenment, or nirvana. Fasting for religious reasons was also prevalent in other parts of the ancient world, including India, China, the Middle East, and Greece.

Fasting and Early Medicine

There is a rich history of leveraging fasting as a natural and easily accessible tool to combat illness and disease. Prior to the advent of the scientific method and germ theory, early medicine was usually more detrimental than the illness or ailment it was trying to treat.

One notable example of this can be found in the records of George Washington’s treatment for what began as an acute sore throat one evening and progressed to shortness of breath by morning. While some controversy remains around his death, the physicians that were called to treat the first U.S. president attempted bloodletting and drained 82 ounces of his blood, or around 50% of his total blood volume.

In contrast, fasting as a form of early medicine was non-invasive and had far fewer adverse effects. It was also a surprisingly effective treatment for an array of conditions, ranging from acute infection to allergies, as well as many diseases known to be resistant to treatment.

Fasting in the 19th and 20th Centuries

By the 19th and 20th centuries, the science of fasting had been confirmed and duplicated as a treatment for many different maladies. Based on historical record and research data, fasting was used to help treat arthritis, asthma, chronic fatigue, high-blood pressure, lupus, Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel, paralysis, and many other conditions.

Historically, fasting was the primary treatment, and often the cure, for both diabetes and epilepsy. We now know that for diabetes patients, fasting helps regulate blood-glucose and insulin levels. In epilepsy, hyperactive neurons that are easily stimulated can be calmed in part by ketones, which are elevated during fasting. Once it was discovered that the ketogenic diet could mimic the ketone production of fasting without the need for calorie avoidance, many people started to embrace ketogenic-diet therapy in place of fasting.

Similarly, once medications that did not require fasting or dietary restriction became widely available, they started to supplant dietary treatments for many diseases, including diabetes and epilepsy. There are many documented stories of practitioners operating clinics relying on natural remedies, such as fasting, that were burdened by fines and imprisonment. Up until recently, there was hostility towards people who used fasting clinically to treat disease, but thanks to an increasing body of scientific research, intermittent fasting is being recognized more and more as a viable therapeutic and health-maintenance strategy.

A variety of short and extended duration fasting strategies are still used today for general health and healing benefits. Despite the popularity of intermittent fasting and time-restricted feeding for goals like weight loss, fasting continues to produce some controversy. There are only a few fasting-focused clinics that exist today, which supervise therapeutic water-only fasts as well as modified fasts with low calorie intake.

Fasting in Modern Times

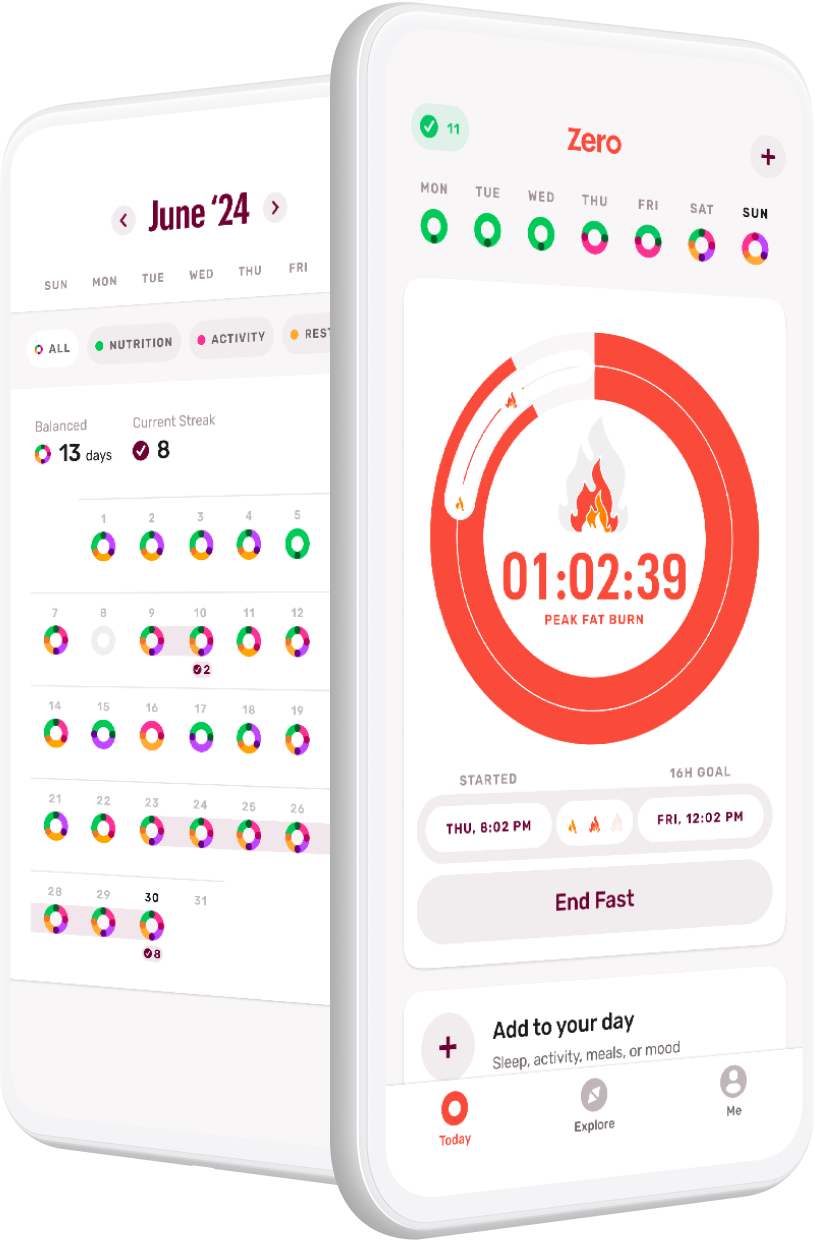

Although fasting is woven into our human biology, it’s still a habit that requires intentionality and consistency to form. In an age where convenience and abundance reign supreme, something like fasting requires considerable effort.

Fortunately, in the last few decades, fasting has risen to prominence once again and gained popularity as an easy and accessible tool for improving one’s lifespan and healthspan. Research continues to demonstrate that fasting is a foundational health habit that can be used to counterbalance modern challenges, like the metabolic-health crisis.

Conclusion

Fasting is a powerful tool with deep roots in human history and a myriad of health benefits. While tradition shouldn’t confine us to any one way of being, fasting has been proven to be effective, and research is still being done to explore all of the ways in which it can help us live healthier, longer lives.

- Debunking 3 Myths Around Fasting and Thyroid Health - April 15, 2024

- Breaking Down Fast Breakers: How to Tell If Something Will Break Your Fast - March 4, 2024

- GLP-1s and Weight-Loss Medications vs. Lifestyle Interventions: What’s Right for You - February 5, 2024