Written and medically reviewed by Katya Meyers, RD

You’ve heard it before: Too much sugar is bad for your health. But, when it comes to the sweet stuff, how much is too much? And what about naturally occurring sugars, like honey and maple syrup? Or zero-calorie alternatives, like aspartame or stevia? Are those healthier or not? With over 60 variations of sugar (and counting!), confusion is pretty much inevitable.

Thanks to the food industry’s incentive to get us to eat more of everything all the time, sugar can be found lurking in everything from desserts to bread and even pasta sauce. Yet even if you could get rid of all those sneaky additions, the reality is that it’s virtually impossible to remove all added sugar from your diet — and we aren’t suggesting that you try! But a better understanding of the facts and fictions surrounding this sugar and its many forms can be an important step in your journey towards weight loss, fat loss, and improved metabolic health.

Sugar vs. Sugar: The Lowdown on “Healthy” Alternatives

With so many types of sugar available, ranging from the naturally occurring sugars found in fruit, vegetables, and dairy, to the many permutations of manmade sugars added to commercial products (e.g., high-fructose corn syrup, dextrose, and rice syrup), figuring out what you’re actually eating can turn into a sticky mess. If you’re trying to reduce your sugar intake, you may have considered sugar substitutes or naturally occuring sugars. But how healthy are these alternatives, really? And, should you be avoiding fruit? Read on to separate fact from fiction.

The 4 Sugar Myths

Myth #1: All Sugars Are Created Equal

There is a difference between naturally occurring sugars, like those already contained in a perfectly ripe banana or a crunchy apple, and those added to foods. This is due to two factors. First, the amount of sugar in a naturally sweet food (e.g., 15 grams in an average banana) is often considerably less than you’ll get with a commercially sweetened food (e.g., 64 grams in a 16 oz soda).

Second, sugars contained in whole foods, like fruits and starchy vegetables, are accompanied by fiber, protein, and/or fats, which help to blunt the impact they have on blood-glucose levels. (Plus you’ll get an added boost of vitamins and minerals packaged in a way your body can more easily absorb!) Keeping blood-glucose levels relatively stable and avoiding large spikes (and crashes) are important not only for those with diabetes, but also for anyone wanting to promote weight loss and fat loss, avoid large swings in energy, and maintain good metabolic health.

The Bottom Line: Added sugar is what you want to reduce, not the sugars naturally occurring in dairy, fruit, and vegetables. Choose whole-food options, like fresh fruit and vegetables, eggs, and roasted nuts over processed foods whenever you can!

Myth #2: Natural Sugars Are Much Better for You

If you google “healthy desserts,” you’ll likely find yourself inundated with recipes calling for ingredients such as honey, maple syrup, agave, or other “naturally occurring” sweeteners. Ultimately, what you should know is that all caloric sweeteners, regardless of their source or chemical composition, contain about 4 calories per gram and will cause a fairly similar increase in blood-sugar levels. This is true even of natural sweeteners, which often confer a bit of a health halo. While sweeteners like maple syrup do contain trace levels of vitamins and minerals and provide a reasonable alternative to plain sugar, they should still be enjoyed in moderation.

The Bottom Line: If you’re going to enjoy a sweet treat, replacing regular sugar with a less processed alternative such as honey or maple syrup may provide a small level of benefit. But, if you aren’t already using them, don’t add them to your diet unnecessarily.

Myth #3: Fruit Is Bad for You

Most of the villainization of fruit comes from the fact that it contains fructose — which, when consumed in excessive amounts, has been linked to obesity and poor metabolic health. However, it’s difficult to ingest high levels of fructose if you’re eating whole fruit. Rather, high-fructose corn syrup (the main sweetener found in things like candy and soda) and sucrose (table sugar, which is made of both fructose and glucose) are the true culprits.

In addition to containing only modest amounts of fructose, fruit comes with added fiber and nutrients, which are essential for health. And more good news: a large-scale meta-analysis of fruit intake demonstrated a positive correlation to metabolic health in a dose-response manner. In other words, those who ate the most fruit were the most metabolically healthy.

The Bottom Line: Fruit often gets a bad rap in the sugar department. But most people can enjoy fruit as part of a balanced diet, knowing it prolongs satiety, provides healthy nutrients, improves weight management, and can help you live a longer life. Stick to whole fruit in its natural form, as fruit juices, fruit concentrates, and dried fruit are far less satiating and can cause larger glucose spikes. If you’re already struggling with metabolic health, use “an apple a day” as your portion, and choose lower glycemic fruits, like berries and melon.

Myth #4: You Get a Free Pass on Zero-Calorie Sugar Alternatives

Non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) are no-calorie or very low-calorie sweeteners that have been developed by the food industry as a replacement for other sugars. They can be either artificial (aspartame, sucralose) or natural (stevia, monk fruit) and are widely available in foods and beverages such as diet soda, low-calorie yogurt, and certain energy bars. However, if sweets that don’t cause weight gain or other side effects sound too good to be true, it’s because they just may be.

NNS are generally recognized as safe and, for certain people, especially those with diabetes, a limited amount of non-nutritive sweeteners may be a better option than regular sweeteners. However, while NNS offer a much lower-calorie alternative to added sugars, their role in metabolic health is far from certain.

Correlational studies have observed a positive association between consuming NNS and weight. In other words, these studies show that those who consume more of these sweeteners often weigh more. While correlation does not equal causation, more tightly controlled studies have also raised concerns about the implications these sweeteners may have for your gut biome, metabolism, and appetite regulation.

For example, in a 10-week study of sucralose, healthy participants who consumed the equivalent of one diet soda per day demonstrated poorer performance on an oral glucose-tolerance test (a measure of how well your body responds to excess sugar) and demonstrated signs of impaired insulin sensitivity. Poor insulin sensitivity makes it easy for your body to gain weight and store fat and, if left untreated over time, can even lead to diabetes. Similar findings have been replicated elsewhere for other NNS, and scientists have proposed that when the sweet sensation received by the brain is unaccompanied by an increase in blood glucose, the body seeks to compensate, leading to metabolic dysregulation and increased hunger.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis examining the effects of NNS on gut microbiota determined that both sucralose and saccharin can lead to adverse changes in your microbiome that are consistent with poorer glucose response in animal models. (Results from human studies remain conflicting.) In light of all of this evidence, guidelines are changing. In fact, the World Health Organization recently discontinued their recommendation that NNS be used for weight management.

However, not all results are so bitter. A recent large meta-analysis put NNS in a more favorable light, concluding that substituting them for regular-calorie foods and beverages yielded mild weight loss and increased compliance with dietary recommendations.

The Bottom Line: The research surrounding NNS is mixed, so limiting your intake is the most prudent approach. Relying heavily on sweeteners — even the naturally occurring ones with zero calories, such as stevia and sugar alcohols — is not recommended.

The 4 Sugar Facts

Fact #1: Sugar Cravings Are Real

Sugar activates the reward system in our brains and has been shown to elicit similar neural activity as addictive drugs. Experiments have shown that chronic smokers can suppress their cigarette cravings better than cravings for refined sugar, and cocaine-addicted rodents have demonstrated preference for saccharin over cocaine. Worse, yet, it is possible to become “sugar dependent,” meaning you need more and more sugar to produce the spikes in these feel-good neurotransmitters.

Stress is one of the most powerful triggers of sugar cravings. In the short term, sugary foods provide quick energy and promote the production of serotonin, an important neurotransmitter for boosting mood. While the immediate result of that sugar rush may be an increase in feelings of happiness, recent research suggests that chronic stress can diminish the brain’s response to eating sugar by deactivating the lateral habenula, the region of the brain that normally responds to sugar by turning off the reward response and signaling satiety when you’ve had enough. In times of chronic stress, the lateral habenula remains silent — encouraging continued eating for pleasure, a.k.a. stress-induced cravings.

Take Action: There is no surefire way to avoid sugar cravings entirely. However, there are tactics you can use to reduce them. Employ mindfulness, get enough sleep, and avoid combining high-stress environments with sugary temptations (e.g., keep the donuts out of the boardroom) whenever you can.

Fact #2: Packing in Protein (and Fiber) Can Help Dull the Spike

Protein is a macronutrient that does a lot of great work for your body. It’s best known for its role in building metabolism-boosting muscle tissue, but it can also reduce the blood-glucose spike that accompanies a high-sugar meal or snack. A study comparing a high-protein breakfast to a higher-carbohydrate breakfast showed improvements in glucose control for the high-protein breakfast, not only at breakfast but also for meals consumed up to 6 hours later.

Fiber, meanwhile, is the structural part of fruits, vegetables, and grains. Although it is a carbohydrate, fiber is not absorbed by the body and therefore doesn’t raise blood sugar. In fact, following a high-fiber diet, especially when the fiber comes in a soluble form from whole foods like oats, carrots, beans, and lentils, has been shown to improve glycemic response.

Take Action: Protein (and fiber!) help to blunt the effects of a high-sugar meal by improving blood-glucose control and increasing satiety. If you know you’re going to enjoy a meal or snack that’s high in sugar, try preempting it with food high in protein and/or fiber. Think orange slices and eggs with your stack of flapjacks, or a few baby carrots and nuts before enjoying a slice of cake at your next party. Keep in mind that opening your eating window with a high-protein-and-fiber Fast Breaker can be a good way to set yourself up for better blood-sugar control (and therefore fewer energy spikes and crashes) throughout the day.

Fact #3: You Don’t Have to Eliminate ALL Sugar, But You Should Probably Reduce It

When it comes to added sugar in your diet, the dose makes the poison. Sugar has been blamed for a host of health problems — obesity, abdominal fat accumulation, and even poor dental health. Having a sweet treat here and there isn’t a problem, but most people are consuming too much… often without knowing it!

The average American consumes an average of 66 pounds of sugar annually. This works out to about 20 teaspoons/80 grams per day — far above the maximums (6 teaspoons/25 grams for females and 9 teaspoons/37 grams for males) recommended by the American Heart Association.

Take Action: When it comes to reducing sugar in your diet, focus on replacing foods containing added sugars with whole-food alternatives. In practice, this looks like sliced strawberries in plain Greek yogurt instead of strawberry-flavored yogurt, herbs and olive oil instead of sugar-laden sauces, or dry-roasted nuts and fruit instead of prepackaged granola bars. No need to go crazy; just start with these easy substitutions and get creative!

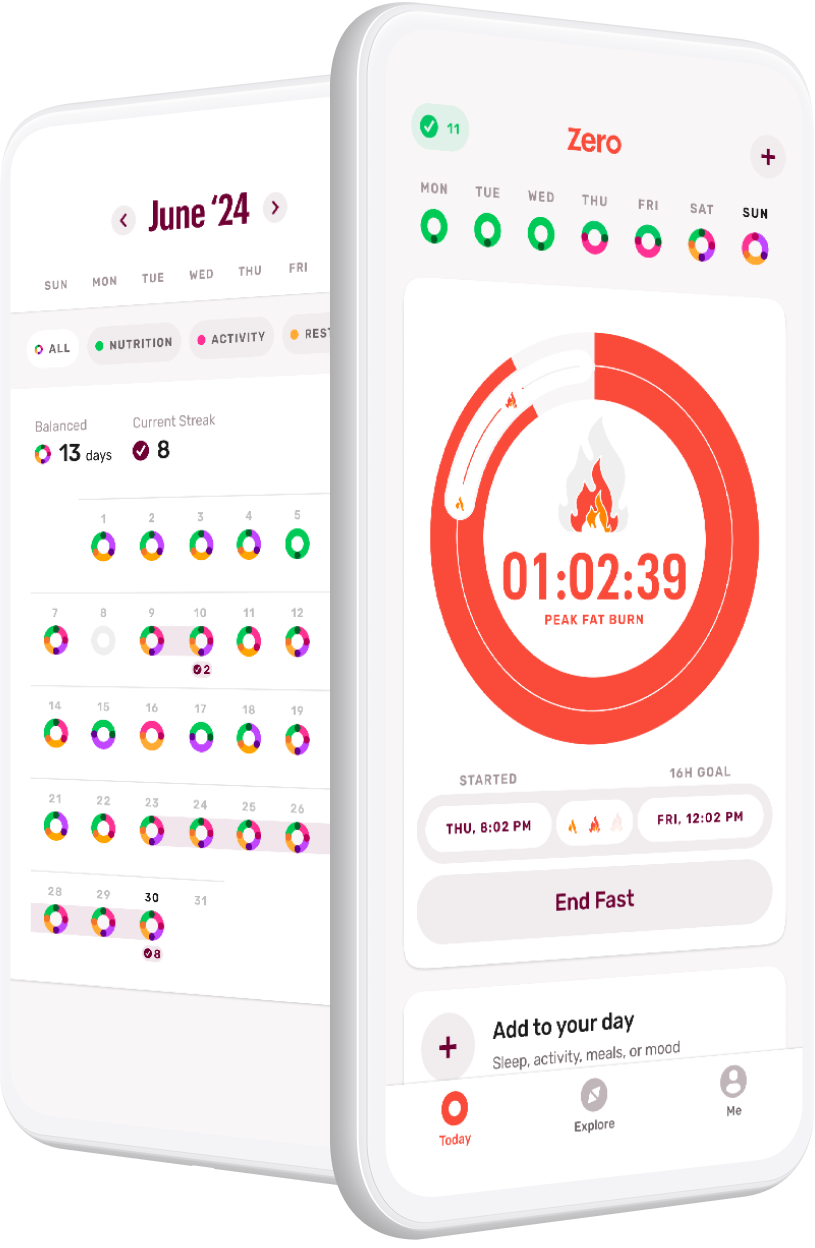

Fact #4: Intermittent Fasting Can Help

If you’re like most people, reducing your intake of added sugars is tough. But here’s some good news: Regardless of where you are on your journey to reduce your sugar intake, expanding your fasting window can help you limit the negative effects too much sugar can have on your health. In fact, research shows that intermittent fasting is an effective way to improve your insulin sensitivity, lose weight, and burn fat. And with better glucose control and fewer energy swings, fasts will get easier and sugar cravings rarer.

Take Action: If you haven’t begun yet, start intermittent fasting! Merely lengthening your overnight fast to 12 hours can start yielding positive effects like improved insulin control. And if you’re already fasting regularly, try extending your next daily fast a bit longer and building your Fast Breaker around healthy protein, fiber, and fat. Before you know it, whole foods and savory meals will be your new norm.

Conclusion: Less Sugar (No Matter the Form) Is Better, and Fasting Can Help

There is no sweet way to say it: Too much sugar is devastating for your health, and you’re probably (perhaps unknowingly!) consuming more than you need. Focus on a whole-foods-based approach, pack in the protein and fiber, and fast for 12–18 hours each day to reduce your reliance on sugar and maximize your metabolic health. By reducing the amount of added sugars you consume — but not fruit; keep eating fruit! — you are taking important strides towards losing weight and living a longer, healthier life.

- The Fasting Guide to Menopause, Perimenopause, and Postmenopause - April 8, 2024

- Try This Instead of That: How to Bookend Your Fasts - March 25, 2024

- 60 Names for Sugar: The Myths, The Facts, and What You Should Know - February 12, 2024