Written and medically reviewed by Rich LaFountain, PhD

Like it or not, humans need rest. Every cell in your body is genetically programmed for activity and rest on a 24-hour circadian cycle, and no amount of “hacking” will keep you healthy if you deviate from that pattern for too long.

Of course, we want to be productive! We need to earn an income and take care of our family and any number of other time-consuming activities that require us to be awake to perform. Still, we are not machines. Therefore, if we want to live long, healthy lives, we need to intentionally find ways to rest and recover from stress. Vacations are an excellent way to do this.

Temporary Stress Versus Chronic Stress

Your body has a difficult time differentiating between types of stress, namely temporary or chronic, because both involve an inflammatory response. Unlike temporary stressors such as injury or illness (which are contained to a specific injury site or time-limited by recovery to full health), chronic stress produces whole-body inflammation with an undefined endpoint.

An easy way to see the effects of chronic stress and inadequate rest is to look at “before and after” comparisons of U.S. presidents. (Although the research suggests that U.S. presidents’ lives are not shortened by their time in office, even if signs of aging appear to accelerate.) Research on cortisol — an important hormone that signals stress throughout your body — explains why this happens.

Researchers have shown that when a person has elevated cortisol over a prolonged period of time, perceived age advances. Cortisol itself is not the problem. Evolutionarily, our stress response was intended to briefly change our metabolism and bodily functions to help us survive illness, danger, and scarcity. There is established research describing how our stress response leads to increases in blood glucose, blood pressure, heart rate, inflammation, all of which are only beneficial on a short time scale. During stress, exercise, or danger, your body undergoes an almost instant shift: cortisol and blood glucose spike, your senses go on high alert, and blood flow to muscles increases to give you enhanced physical abilities—collectively these changes are known as the “fight or flight” response. However, if sustained without interruption, our stress response tips the scales toward systemic inflammation and elevated risk of chronic disease, neither of which is good for longevity.

There are many well-known downstream effects of chronic stress that contribute to reduced healthspan and lifespan including impaired cardiovascular, hormonal, and immune system function. Less often discussed is the loss of circadian rhythm that occurs when cortisol remains elevated for too long. But what qualifies as too long? Research defines chronic stress as a stressor that persists for months on end or a stress response to an acute scenario that persists for weeks. However, there isn’t strong scientific consensus around a more specific duration because stressors and stress resilience affect each person differently.

If you want to prevent the detrimental effects of chronic stress, you need to be able to identify and avoid it. Chronic stress often originates from psychosocial stressors including work, finances, adversity around major life events, and burnout. Even repetitive, otherwise positive temporary stress, like exercise, can become a chronic maladaptive stress known as overtraining syndrome when it is not balanced with adequate rest and quality nutrition.

Considering much of our lives will be impacted by stress, both temporary and chronic, we need to attend to our stress-rest balance. Getting quality sleep is one important way to fulfill rest requirements. Vacations are another.

Managing Chronic Stress with Vacations

Chronic stress isn’t necessarily the most intense stress, but because it’s ongoing, its effects can compound over time. Therefore, you’d be wise to take advantage of opportunities like vacations to break the continuity of stress associated with busy schedules, deadlines, and overlapping demands of time, money, work, and social responsibilities.

Traditional vacations—the sort where you leave home for several days—are quite literally good for you. A long term follow-up study found that individuals who vacationed an average of more than 21 days per year had 10-15% lower likelihood of dying over the next 30 years. Unfortunately, adults in the U.S. average only one or two vacations each year totaling 10 days or less. If your job gives you more vacation days, do your best to take them!

Vacation Microstructures for When You Can’t Get Away

Given that we can’t always go on multi-day trips to break the cycle of chronic stress, it’s necessary to find other ways. Interestingly, vacations have structure, and we can use the elements of this structure (microstructures) to help decrease stress in our everyday lives. The goal is to make a habit of dedicating a portion of your day-to-day activities that promote and support rest from daily stressors. Such activities can include mindfulness or meditation practices, leisurely physical activity, socialization, and nature-based recreation.

Don’t Forgo “Good Stress” + Necessary Recovery

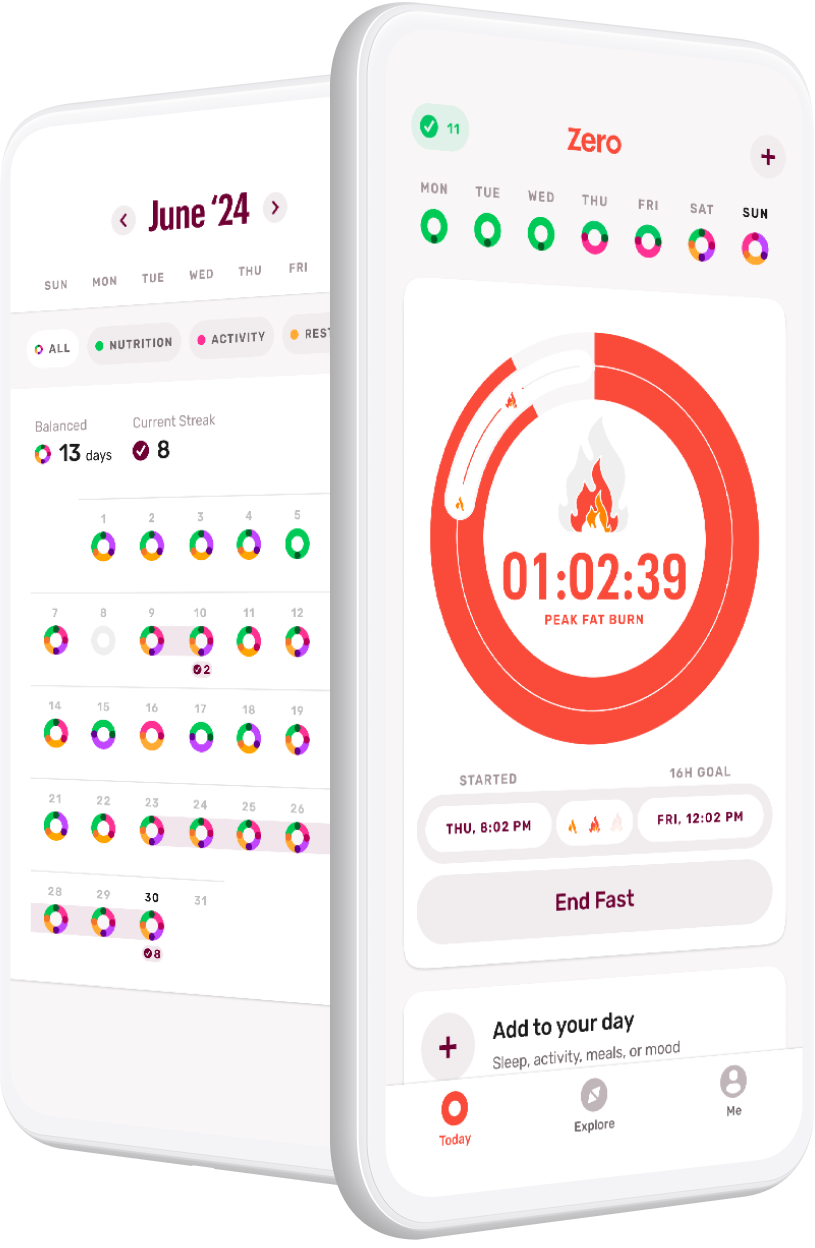

Stress is inevitable, but it’s not all bad. We know that uninterrupted chronic stress is not healthy and certainly not optimal for longevity. Yet, data suggest that many short-term exposures to stress, followed by adequate recovery, can improve resilience and longevity. The scientific term for this process is hormesis. Examples of hormetic stressors include exercise, cold exposure, fasting, and even hypergravity, all of which challenge or stress your body but can be turned on and off strategically to allow for rest.

The key to making hormesis work is to balance the stressor with appropriate rest. Whether your goal is to run a marathon or be a supercentenarian, rest and recovery are crucial for your body to rebuild what the stress broke down—and to rebuild it stronger. Consider the marathon example: If you decide to run a marathon in six months, you’ll need to spend that time gradually running more miles until you can complete the full 26.2 on the day of your race. However, if you spend the time leading up to the race focusing exclusively on training, i.e., neglecting essential components of recovery like nutrition, sleep, and just plain rest, you risk missing your target due to illness, injury, or overtraining syndrome. Likewise, if your goal is peak longevity but you forgo vacations in lieu of constant work, you again run the risk of missing your target. You must balance stress, which produces improvement signals, with rest, which allows space for improvement processes to occur.

Ultimately, if we’re going to maximize our longevity, we need regular reprieves from the chronic stressors in our lives. Vacations are a great way to do this. And while week-long trips to snow-capped mountains or sunny beaches are fun, daily vacation microstructures can go a long way towards reducing stress, improving rest, and helping us recover so we’re ready to take on whatever might happen next.

References

Segerstrom, S. C., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological bulletin, 130(4), 601–630.

Black P. H. (2002). Stress and the inflammatory response: a review of neurogenic inflammation. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 16(6), 622–653.

Olshansky S. J. (2011). Aging of US presidents. JAMA, 306(21), 2328–2329.

Noordam, R., et al. (2012). Cortisol serum levels in familial longevity and perceived age: the Leiden longevity study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(10), 1669–1675.

Marik, P. E., & Bellomo, R. (2013). Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response!. Critical care (London, England), 17(2), 305.

Sapolsky, R. M., Romero, L. M., & Munck, A. U. (2000). How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocrine reviews, 21(1), 55–89.

Couzin-Frankel J. (2010). Inflammation bares a dark side. Science (New York, N.Y.), 330(6011), 1621.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological Stress and Disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687.

Miller, G. E., & Blackwell, E. (2006). Turning Up the Heat: Inflammation as a Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 269–272.

Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Zhou, E. S. (2007). If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological bulletin, 133(1), 25–45.

Hammen, C., Kim, E. Y., Eberhart, N. K., & Brennan, P. A. (2009). Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depression and anxiety, 26(8), 718–723.

Russo, S. J., Murrough, J. W., Han, M. H., Charney, D. S., & Nestler, E. J. (2012). Neurobiology of resilience. Nature neuroscience, 15(11), 1475–1484.

Hänsel, A., Hong, S., Cámara, R. J., & von Känel, R. (2010). Inflammation as a psychophysiological biomarker in chronic psychosocial stress. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 35(1), 115–121.

Angeli, A., Minetto, M., Dovio, A., & Paccotti, P. (2004). The overtraining syndrome in athletes: a stress-related disorder. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 27(6), 603–612.

Strandberg, T. E., Räikkönen, K., Salomaa, V., Strandberg, A., Kautiainen, H., Kivimäki, M., Pitkälä, K., & Huttunen, J. (2018). Increased Mortality Despite Successful Multifactorial Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Healthy Men: 40-Year Follow-Up of the Helsinki Businessmen Study Intervention Trial. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 22(8), 885–891.

Hyde, K. F., & Laesser, C. (2009). A structural theory of the vacation. Tourism management, 30(2), 240-248.

Bohlmeijer, E., Prenger, R., Taal, E., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: a meta-analysis. Journal of psychosomatic research, 68(6), 539–544.

Iwasaki, Y., Zuzanek, J., & Mannell, R. C. (2001). The effects of physically active leisure on stress-health relationships. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique, 92(3), 214–218.

Heinrichs, M., & Gaab, J. (2007). Neuroendocrine mechanisms of stress and social interaction: implications for mental disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry, 20(2), 158–162.

Hull IV, R. B., & Michael, S. E. (1995). Nature‐based recreation, mood change, and stress restoration. Leisure Sciences, 17(1), 1-14.

Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social, Psychological, and Biological Pathways. Bethesda, Maryland, USA. May 10-12, 1999. Proceedings. (1999). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 1–503.

Schetter, C. D., & Dolbier, C. (2011). Resilience in the Context of Chronic Stress and Health in Adults. Social and personality psychology compass, 5(9), 634–652.

Rattan S. I. (2008). Hormesis in aging. Ageing research reviews, 7(1), 63–78.

Schoenhofen, E. A., Wyszynski, D. F., Andersen, S., Pennington, J., Young, R., Terry, D. F., & Perls, T. T. (2006). Characteristics of 32 supercentenarians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(8), 1237–1240.

- Debunking 3 Myths Around Fasting and Thyroid Health - April 15, 2024

- Breaking Down Fast Breakers: How to Tell If Something Will Break Your Fast - March 4, 2024

- GLP-1s and Weight-Loss Medications vs. Lifestyle Interventions: What’s Right for You - February 5, 2024